Your metabolism is a complicated subject, and frequently misunderstood. Yet understanding how it works—at least basically—can make you feel tremendously more comfortable with your diet, because your metabolism is at the heart of whether you gain, lose, or maintain weight.

Most people think of the relationship between weight loss and weight gain as dichotomous, with only a thin swath known as “weight maintenance” dividing the two. And almost invariably, they assume that this swath is closer to the weight loss end of the spectrum than the weight gain end, or at least that they’re better off maintaining weight on fewer calories rather than more. They short themselves, and end up shorting their performance as well.

Weight loss and weight gain are not so narrowly divided, however; it’s not as much a balancing act as you may believe. Your metabolism is a bit more “wibbly wobbly” (to use an official term from Doctor Who). Yes, there are concrete points we could scientifically determine with enough information—points at which you will either gain or lose weight, fat, and protein—and yes, your basal metabolic rate (BMR) is static (or near enough to). But when the whole of your diet and lifestyle is considered, there is a lot more give in the system, and this give makes your effective needs for weight maintenance a bit more open.

What Your Metabolism Is Not

Your metabolism is not a line dividing weight loss from weight gain that you’re always trying to straddle and stay balanced on; it’s a continuum ranging from a dangerous caloric deficit (where muscle protein breakdown and eventually organ protein breakdown occurs in addition to fat loss) to weight maintenance to a dangerous caloric excess (where adipose tissue is stored in addition to muscle tissue). You might not even realize that this is how you view your metabolism, but it’s a fairly common belief.

As an example, it’s the root of the idea that long-term weight gain is caused by eating just a little too much every day until suddenly, ten years down the line, you’re ten pounds heavier than you used to be. If you believe this is true, then all it would take is eating 10 calories too many daily, which is roughly equivalent to a single potato chip. It seems ridiculous when you break it down like this, but that’s what having a narrow line dividing weight loss and weight gain would look like!

Because many climbers see their metabolism (and weight maintenance) as a balancing act, they downplay how many calories they can actually eat and still maintain weight. In fact, it often works in a negative feedback cycle, where an individual lowers their calories, then doesn’t lose weight, and so drops their calories further and further until weight loss finally kicks in.

The problem is that while this is an essentially fine strategy for weight loss (you need to reduce calories to lose weight), it’s easy to forget that you can maintain weight with a far greater number. Once you either reach your target weight or give up on the weight loss, you never increase calories back to a healthy maintenance pount; instead, you forever hover near (but not quite at) the weight loss threshold.

It’s easy to understand how this can happen, but it’s not necessary—and it can be unhealthy. At the very least, it’s not good for performance because you’re only giving your body the bare minimum it needs to maintain the status quo; it simply doesn’t have the surplus to recover effectively or improve.

What Your Metabolism Actually Looks Like

Your metabolism runs a gamut from extreme to extreme with numerous physiological pitstops in between.

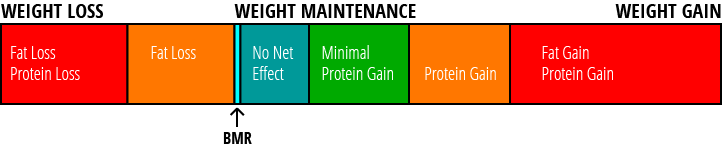

If we use our basal metabolic rate (plus activity calories) as the starting point, then we might section the gamut as so:

Basically, it’s better to think of your BMR as a minimum for weight maintenance, because once you tread under it your body will be required to derive its energy from some other source (i.e., your stored tissues, primarily fat) to maintain normal function—but going over your BMR does not guarantee weight gain because there are numerous other areas to divert spare calories aside from fat. These areas include, but are not limited to:

- Protein Gain (e.g., muscle growth, tendon growth, ligament growth, etc.)

- Glycogen Gain

- Tissue Repair

- Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT)—i.e., fidgeting

So when you eat more calories, you allow your body to do all the functions that aren’t really essential—you won’t die without them—but which are often critical to performance and success, such as expanding your intramuscular energy stores (both carbohydrates and fats), developing your muscles, strengthening your connective tissue, and repairing damaged tissues in a timely manner. And even if you still have calories to spare, we all have (to a greater or lesser extent) a built-in safeguard to burn those unneeded calories: fidgeting. (The reverse of this is true as well: if you consume too few calories, your body may decrease non-exercise activity, minimizing the effect of your caloric deficit.)

As a final point, we also need to consider that “weight” can be maintained even when muscle (or fat) grows (or shrinks). If you diligently train—and especially if you’re relatively new to training or climbing—you can gain a large amount of muscle without gaining weight because that muscle is offset by fat loss. Conversely, if you were to stop climbing (and exercising in general) for five years, but kept a similar diet, you might lose muscle and gain fat, all the while never seeing the scale’s needle budge.

Thus, “weight maintenance”—which is distinct from “fat maintenance” or “muscle maintenance”—can occur in an even larger variety of ways than the graphic above portrays. If you’re ever trading one tissue type for another in equal (or near equal) amounts, then your scale won’t reflect any change even though a lot is happening!

At any rate, the number of calories you can eat and still maintain weight occupies a larger range than you may suspect, and my recommendation is to slowly increase calories until you start gaining weight, then back off a bit (rather than the opposite). You still won’t gain weight, but you’ll perform better, recover faster, and are much more likely to trade fat for muscle.

Summary

There are two ways you can maintain weight as a climber:

- You can reduce calories as much as you can before beginning to lose weight and hold steady there.

- You can increase calories as much as you can before beginning to gain weight and hold steady there.

Of the two, the latter is far preferable because you allow your body the spare calories to do more than its basic (basal) functions.

Regardless, what divides weight loss from weight gain is not a thin line—it’s a sometimes sprawling territory. If you’re anywhere within the bounds of this territory, you’re going to maintain weight… but it’s up to you to decide whether you’d rather be on the near or far side of performance!